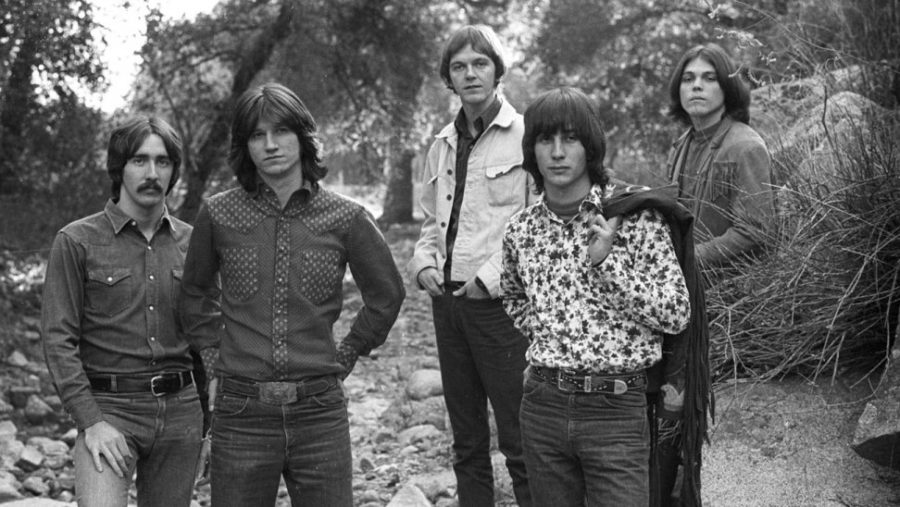

Between recording their second and third albums, the Doobie Brothers had been on a roll. The band’s 1971 debut studio album, self-titled The Doobie Brothers, wasn’t met with great success, selling maybe 40,000 to 50,000 copies, according to guitarist Pat Simmons.

But their second album, Toulouse Street, released in 1972, was the band’s entry into the national marketplace, and secured the Doobie Brothers their first major national tour, opening for Marc Bolan and T. Rex.

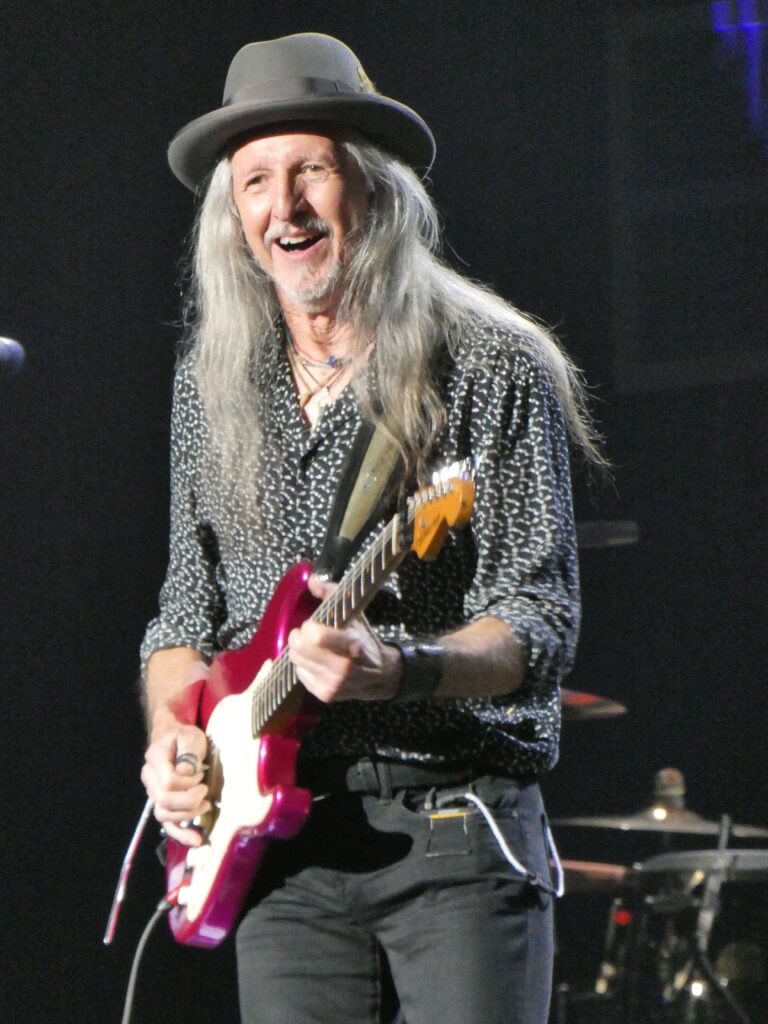

“That was a big moment for us because we were sort of the new kids on the block and that introduced us to a much larger audience,” said Simmons, one of the original co-founders of the band. “We had these hits off Toulouse Street — ‘Listen to the Music,’ Jesus Is Just Alright,’ and ‘Rockin’ Down the Highway,’ — that got played quite a lot.”

Simmons and fellow original Doobie Brothers … Read more