Between recording their second and third albums, the Doobie Brothers had been on a roll. The band’s 1971 debut studio album, self-titled The Doobie Brothers, wasn’t met with great success, selling maybe 40,000 to 50,000 copies, according to guitarist Pat Simmons.

But their second album, Toulouse Street, released in 1972, was the band’s entry into the national marketplace, and secured the Doobie Brothers their first major national tour, opening for Marc Bolan and T. Rex.

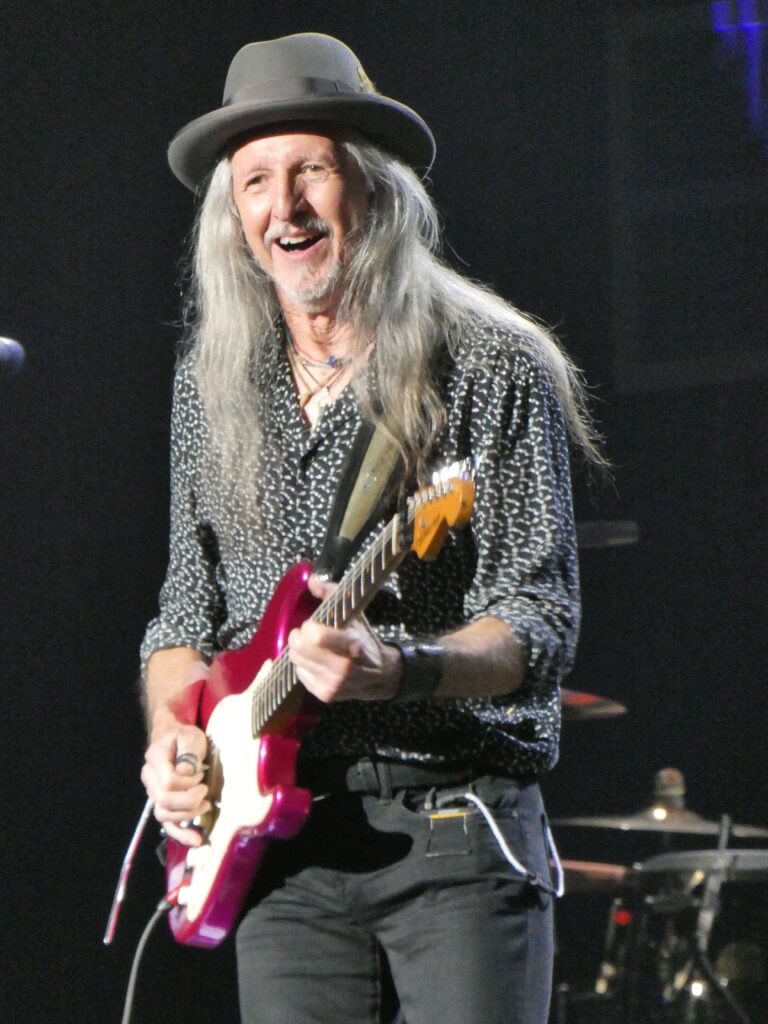

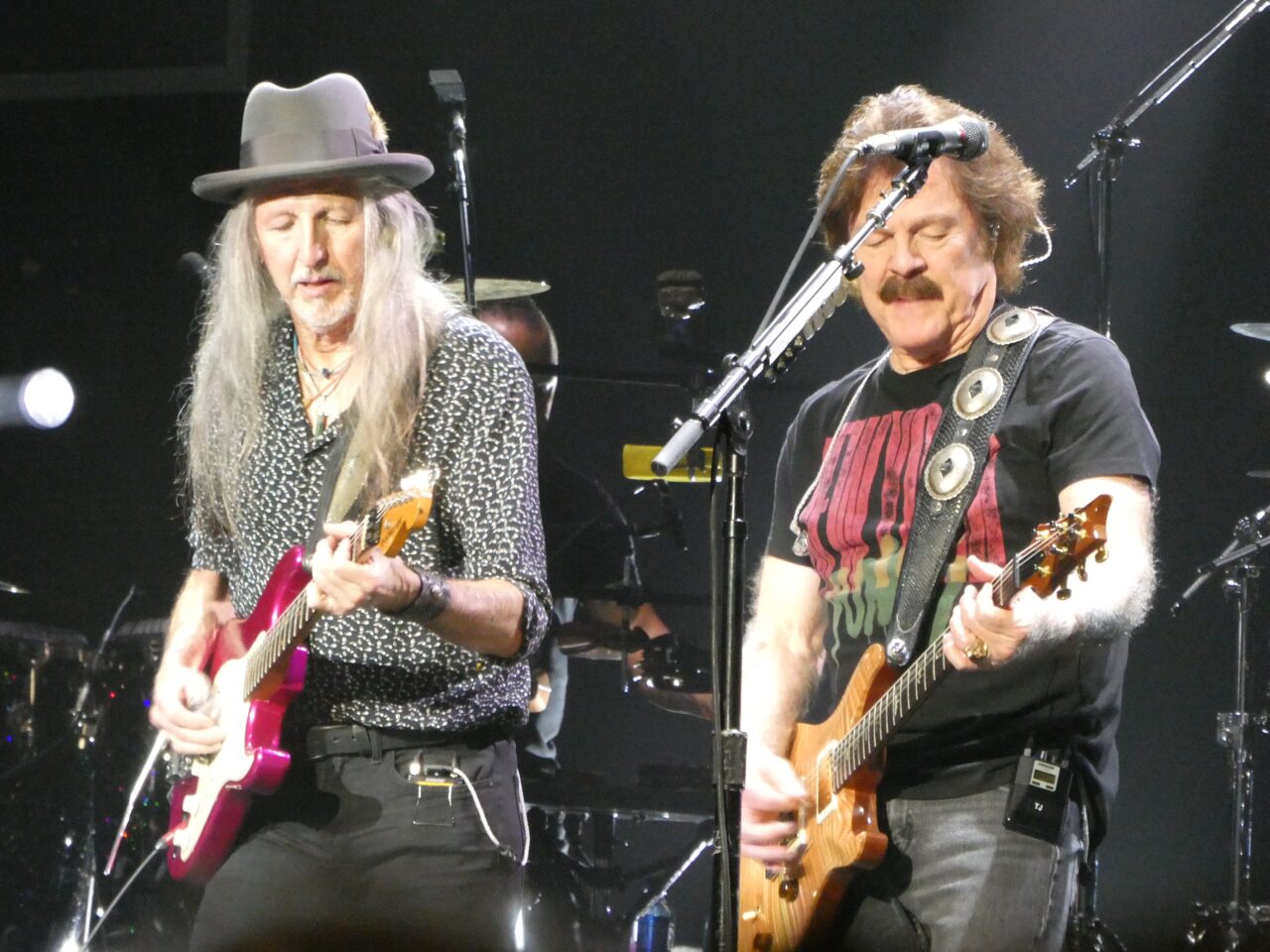

“That was a big moment for us because we were sort of the new kids on the block and that introduced us to a much larger audience,” said Simmons, one of the original co-founders of the band. “We had these hits off Toulouse Street — ‘Listen to the Music,’ Jesus Is Just Alright,’ and ‘Rockin’ Down the Highway,’ — that got played quite a lot.”

Simmons and fellow original Doobie Brothers co-founder Tom Johnston had each written quite a few songs, even prior to recording Toulouse Street, that didn’t make the cut for that album, so they were looking forward to getting back into the studio and recording their third album in late 1972.

One song that didn’t make the cut for Toulouse Street was “Long Train Runnin’,” a song that the band had played many times onstage that had no real structure to it. It didn’t have any lyrics, either.

“Tommy would get up and just kind of scat through it and sing the blues. He’d take a guitar solo and I’d take a guitar solo and we’d just play it out as a funky groove, sort of a Latin funk. And we’d just sort of jam along,” said Simmons.

Producer Ted Templeman would offer direction. He suggested that words be put to the jam before the band recorded it at what was then called Amigo Studios, a division of Warner Brothers, in North Hollywood, California.

“The solo itself became a harmonica solo, which was kind of cool,” said Simmons. “We didn’t have that in the original arrangement, which was a lot of guitars.

“I sat in with Ted for a while, while the guys were working on the track — bass drums, guitars — and then I went into an adjacent space in between the walls and I took my acoustic guitar and I started playing around,” said Simmons. “And I came up with my part while the guys were cutting the track. As soon as the track was cut, I went in and laid down my track.”

Simmons said the song was kind of a straight-ahead, blues-rock tune.

“It was something we could all sink our teeth into,” he said. “We had been playing the tune for the better part of two-and-a-half to three years on and off in our club sets, but we really didn’t have this creative arrangement. It really came to life not only as a studio track, but as a live tune. We got something really cool out of it, and to this day, we still play the track. It’s the highlight of our set, I think.”

“Long Train Runnin’” peaked at No. 8 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1973.

Another song from The Captain and Me that ended up as a Top 20 single — reaching No. 15 — was “China Grove.”

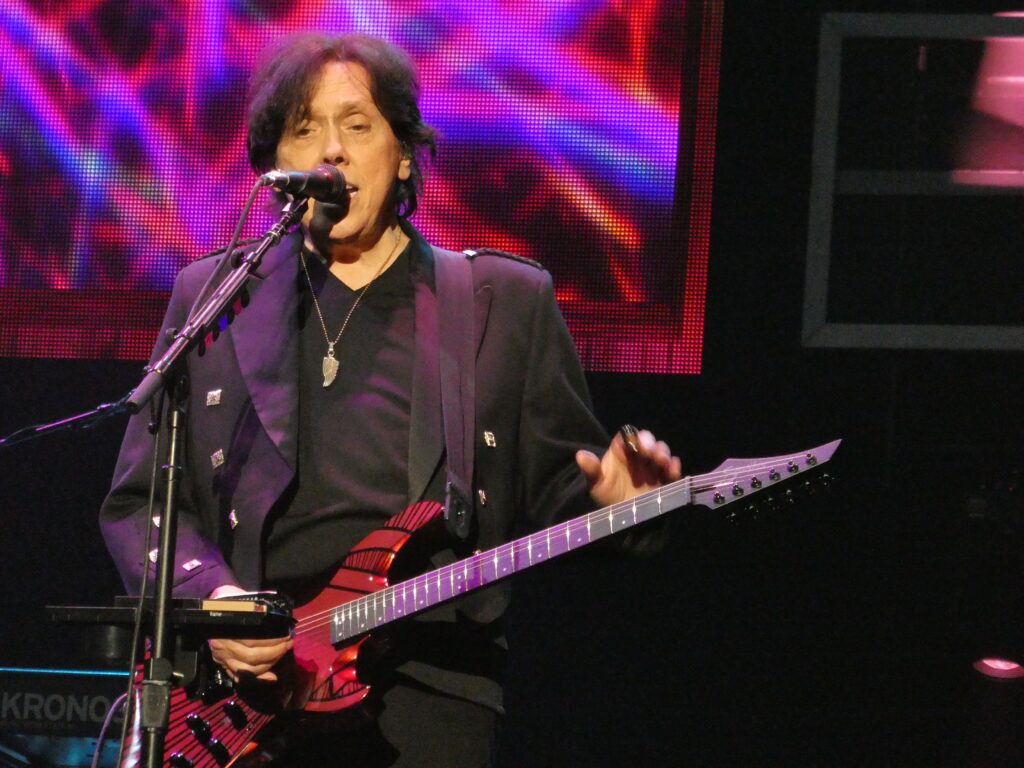

According to Johnston, the band was touring in a Winnebago in 1972 and had just started to get national recognition. While driving through Texas, they passed a road sign that read “China Grove.”

“But I didn’t see it, or if I did, I didn’t remember it,” said Johnston. “We were headed into San Antonio at the time and my thinking was that I saw the name ‘China Grove’ without having it really register in the frontal lobe.”

Johnston wrote the song in early 1973 based on a piano lick by Billy Payne.

“And I made up all these ridiculous lyrics about sheriffs and samurai swords and all that kind of stuff,” said Johnston. “But at that time, I still believed it was a completely fictional place.”

In 1975, Johnston got into a cab in Houston, Texas. He and the cabdriver struck up a conversation, and once the cabbie realized that Johnston was a member of the Doobie Brothers, he posed a question.

“He said, ‘What made you write a song about that little old town, China Grove?’ I said, ‘What town, China Grove? I’ve never heard of a town called China Grove.’ He said, ‘Yeah, it’s right down there, like the song says, right outside San Antonio.’ That blew me out of the water, it really did,” said Johnston. “That was a trip. I thought he was pulling my chain.”

Although none of the other songs on The Captain and Me charted as singles, the hidden gem may be the Simmons-penned song, “South City Midnight Lady.”

Simmons said that the band had a sense that some songs — like “Long Train Runnin’” and “China Grove” — had commercial appeal and the potential to get wide play on the radio. But “South City Midnight Lady” was what the band members called an “album track,” and not a commercial type of song.

The song is about living in Los Gatos, California, which is at the southern end of the bay area. Simmons was living with his girlfriend at the time and was trying to write a romantic song.

“I don’t necessarily look at it as that personal, but it probably is,” said Simmons. “I was up all night writing that song. By 4 or 5 in the morning, I was pretty much finished with the song and I had the arrangement idea pretty much together.

“It was interesting because a friend of mine showed up in the morning and knocked on my door. It was pretty early, around 7 a.m., and I was surprised that he showed up that early. And he was surprised I was awake that early, but in fact I had been up all night,” said Simmons.

“I remember playing the song for him and him liking it and then I think I went to bed. I can’t even remember if my girlfriend liked the song, but I’m sure she thought it was OK.”

There is one song on Side Two of The Captain and Me that seems to be an odd fit. It’s a 48-second guitar instrumental track titled “Busted Down Around O’Connelly Corners.” The song is listed on the record between “Evil Woman” and “Ukiah,” but one has to actually look at the record itself to know that the song is there. It’s not listed on the back of the album cover.

“That was a tune that a friend of mine had written,” said Simmons. “There’s actually more to it than what’s on the record.”

Before he joined the Doobie Brothers, Simmons hung out in southern California perfecting his craft. After playing club gigs, Simmons and his friends would oftentimes head to another friend Mike O’Connelly’s place, in an apartment building on Main Street in Los Gatos to relax, play their guitars, and sing.

“We’d sit around and somebody would play a song and the rest of us would sing along. It was kind of like a poor man’s Bluebird Cafe,” said Simmons, referring to the famous club in Nashville, Tennessee, that attracts singers and songwriters to its intimate setting.

They’d hang out at Mike’s place so much that they started referring to the apartment building as “O’Connelly Corners.”

“One time Mike had walked outside the apartment building and was getting in the car to go someplace,” said Simmons. “He had a joint on him or something, and the cops arrested him.” And that was the inspiration for the song “Busted Down Around O’Connelly Corners,” written by James Earl Luft.

By the time the Doobie Brothers were recording The Captain and Me, producer Ted Templeman had become a big fan of Simmons’ “traditional ragtime guitar picking.”

“So Ted said, ‘Hey, Pat, you got something else you can put on this album,’” recalled Simmons.

And that’s how the first 48 seconds of “Busted Down Around O’Connelly Corners” made it onto Side Two of The Captain and Me.

Album covers of that era were oftentimes considered works of art that complemented the songs on the album, and The Captain and Me is no different.

Simmons said the band members used to sit around and conceptualize ideas for album covers. Doobie Brothers drummer John Hartman was always an idea guy, according to Simmons.

“He was a little eccentric and he liked to come up with crazy concepts, musically and visually,” said Simmons. “We were brainstorming one time — we used to sit around and smoke … something … well into the night.

“We had several ideas floating around and we came up with the idea of the coach and the outfits — sort of the Old English or early American formal wear, that really didn’t mean anything. We just thought, ‘What would that be like?’”

Luckily, the Doobie Brothers were under contract to Warner Brothers, a company that, in addition to producing music, also produced films.

Hearing about the band members’ idea of dressing in old formal wear, Templeman’s production assistant, Venita Brazier, went to Warner Brothers’ costume department. Armed with the sizes of each band member, she found the appropriate coats, shirts, hats — everything the Doobie Brothers needed for the photo shoot.

Not only did Brazier gather the clothes, but she also got hold of the coach, the horses, and, along with the band’s then-manager Bruce Cohn, scouted the perfect location for the photo session: Interstate 5 on the way out of Los Angeles, a stretch called “The Grapevine” on the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley.

A few years earlier, an earthquake had knocked down parts of the freeway, and Brazier had somehow secured permission from the proper authorities to use a not-yet-repaired section of the fallen freeway for The Captain and Me photo shoot.

“We thought it was a unique spot, so we got up next to the highest part of the freeway that was being rebuilt,” said Simmons. “Handlers from Warner Brothers brought out the horses and the carriage. It was probably the most expensive album cover ever.

“We shot it in one day. It worked real well, though,” said Simmons. “Tommy had written this song called ‘The Captain and Me,’ which was kind of a poetic, obtuse song. So we looked through the titles of the songs and we thought that it definitely worked in terms of this obscure reference to the captain. Who is the captain? I don’t know. But it worked with the visual somehow and with how it all went down. It was kind of like these guys came in a time machine and landed on the freeway.”

Nearly 50 years after the release of The Captain and Me, Simmons called it “a moment in time when we were hitting on all cylinders.”

“There are a lot of great tracks on that record that we still enjoy playing live,” he said. “At some point, songs from all our albums are incorporated as we go along into our shows now. But that record always seems to have certain songs that always turn up in the set, simply because they’re more iconic or they’re what people expect to hear.

“And we enjoy playing them because there’s that moment of connection, to see the recognition on people’s faces. That really means a lot to us as performers,” said Simmons.

Things began to change for the Doobie Brothers by the end of 1974. Life on the road had taken its toll on Johnston and by the spring of 1975, his health was so precarious that he was hospitalized with a bleeding ulcer.

Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, co-lead guitarist for Steely Dan until Donald Fagen and Walter Becker decided to quit touring in 1974, had joined the Doobies that same year as third lead guitarist.

Baxter had already been working with the Doobies off and on for a few years, contributing a steel pedal guitar on “South City Midnight Lady” for the Captain and Me album and on the band’s first No. 1 hit, “Black Water,” written by Simmons for the What Once Were Vices Are Now Habits album in 1974.

When Johnston fell ill and couldn’t tour with band, it was Baxter who recommended that fellow Steely Dan songwriter and keyboardist Michael McDonald join the group.

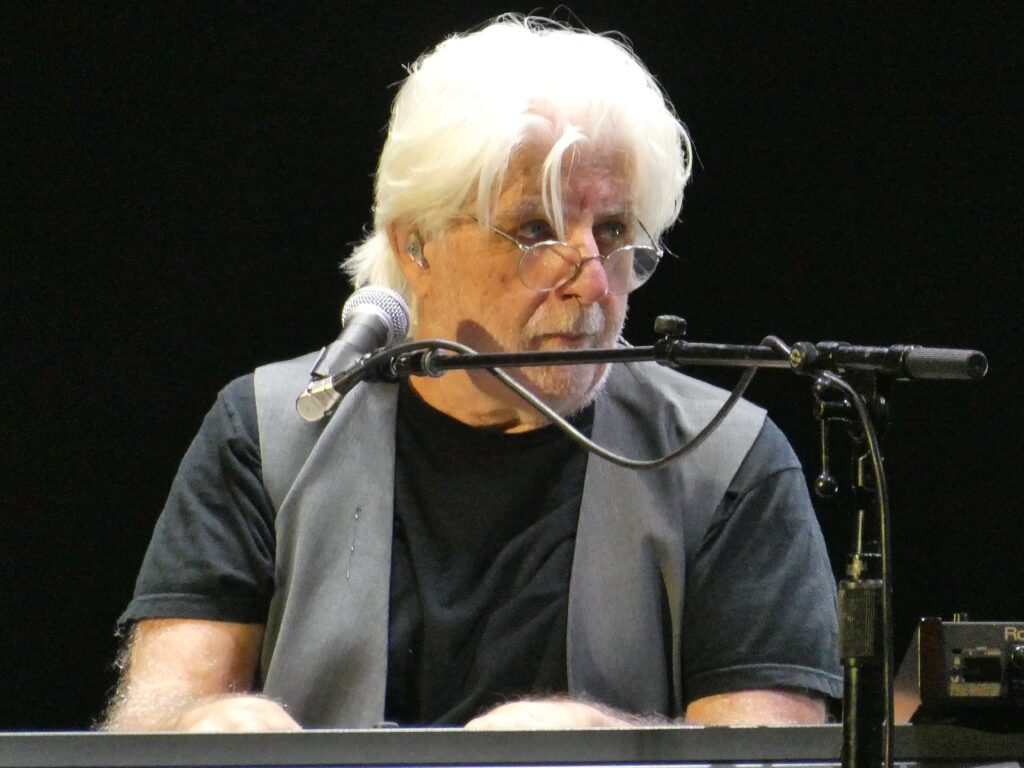

“When I joined, I thought it was going to be a two- to six-month gig. I thought I’d better save my money because I wasn’t going to make this much money for a while,” said McDonald. “That’s how I lived as musician back then. If I was making a good payday for a while, I didn’t spend it all. I was living pretty much hand-to-mouth.”

According to McDonald, nobody knew what was going to come next for the Doobie Brothers. But with the absence of Johnston and the addition of McDonald, the band was changing.

McDonald credits Baxter with playing an integral part in that change.

“Jeff was a big part of bringing me not only into the band but of the music changing,” said McDonald. “The arrangements of our songs and his guitar style and jazz influences brought a lot to the band and to my songs.”

More importantly, McDonald said, was that Simmons and the rest of the guys in the band were on board with the band’s change of musical direction.

“One of the biggest components in all of this was really the absence of Tommy because he was such a huge influence in the direction of the band up to that point,” said McDonald. “Just by the virtue of him taking a hiatus and being gone from the next recording, that left a big hole, for better or worse. But it was a collective effort to try and fill that void that was responsible for the band changing.”

Johnston hadn’t actually quit the band at that point; he just needed to get off the road and away from it for a while. Warner Brothers was leery about the next album, Takin’ It To The Streets, released in March 1976, which would be the first album to feature McDonald on lead vocals and take the band in a completely different direction.

But the title track, written by McDonald and with him on lead vocals, went to No. 13 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, and another McDonald-penned song, “It Keeps You Runnin’” made it to No. 37 on the same chart. The strength those two songs propelled the album to No. 8 on the Billboard Pop Albums chart.

McDonald said that the idea behind “It Keeps You Runnin’” — that love can be a traumatic experience — was one that he had written and rewritten many times.

“Every time you go through it, it reshapes you in a different way. There’s post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress that comes from love,” said McDonald. “It’s kind of finding that balance between the two as you go on in your life. Learning to be a little more accepting of love on its own terms with each time. And at the same time, not gaining an overall phobia of the thing to where you avoid it at all costs. It’s just kind of learning how to ease back into something that you know has consequences. You don’t want to get too pessimistic about it as you go through life.”

The idea for “Takin’It To The Streets” came to McDonald as he was driving through Southern California on the way to a gig.

“I just heard the intro in my head and I knew that it had something to do with a gospel kind of feeling track,” he said. “I couldn’t wait to get to the gig so I could figure out on the piano what it was.”

Once at the gig, McDonald set up his piano as fast as he could, plugged everything in and then just sat there for a moment, looking for the chord that he was hearing in his head.

“I just picked at it long enough to where the guitar player said to me, ‘Hey, we gotta start.’ I was lost in looking for this elusive melodic rhythmic song,” he said. “Basically the song kind of happened in those couple of minutes. The rest of the song was pretty simple. It was just trying to figure out what that intro meant and where it was going musically.”

The lyrics for “Takin’ It To The Streets,” followed soon thereafter. McDonald had been talking to his sister, who was a college student at the time.

“She was in a social economics class or something, and she was a typical college student, and the weight of the world’s problems were solvable by those as smart as college students,” said McDonald. “We talked about how in the inner city, the bottom was dropping out for people and they were falling through the cracks. So when I sat down to finish the song once I got home to my apartment that night, it just seemed like that was a natural marriage of ideas and melody.”

McDonald and the Doobies didn’t recapture the magic again until December 1978, when the band released its eighth studio album, Minute by Minute.

It would be the band’s first album without any contribution from Johnston, and the last album to feature Baxter and John Hartman as members of the group.

But it provided the Doobies with their second No. 1 single, “What a Fool Believes,” sung by McDonald and co-written by McDonald and Kenny Loggins; and the title track, co-written by McDonald and Lester Abrams, that reached No. 14 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.

The album itself would get to No. 1 on the Billboard Pop Albums chart in 1979, spending 87 weeks there. In the spring of 1979, the album was the best-selling record in the U.S. for five consecutive weeks and was eventually certified 3x platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America.

The Minute by Minute album would also win a Grammy for “Best Pop Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group”; and “What A Fool Believes” earned the band three Grammys, including Song of the Year and Record of the Year.

McDonald and Loggins had never written together — in fact they had never even met — before collaborating on “What A Fool Believes.”

Doobies bassist Tiran Porter had run into Loggins during his travels and Loggins told Porter he was interested in writing with McDonald. So Porter passed along Loggins’ phone number to McDonald.

“I called Kenny and we made a date to get together,” said McDonald. “I had never met the guy and I was kind of nervous. He was coming to my house and my sister came over to clean up because it was usually pretty trashed and because she decided she was going to meet Kenny Loggins and thought that at the very least, I shouldn’t have my dirty laundry in a pile in the living room.”

While his sister was hustling around cleaning the place and doing the laundry, McDonald was sitting at his piano playing around with a riff and verse that had been in his head for a while but hadn’t gone anywhere.

“I knew there was something to it, but I just never had the wherewithal to finish the song,” said McDonald. “I had played the riff for producer Ted Templeman a few times and he said it was something that I should finish.”

McDonald was doodling with that riff when Loggins rang the doorbell.

“He had driven down from Santa Barbara. When I opened the door, and before I could say anything, Kenny said, ‘You were just playing something on the piano. Is that something new?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I was thinking about playing it for you.’ And he said, ‘That’s the one I want to work on,’” said McDonald.

Over the next two days, the two worked on the song. They came up with the bridge and chorus and the rest of the lyrics.

“We got as far as the bridge on the first day and we weren’t sure what to do in the chorus,” said McDonald. “We stumbled into the chorus on the next day and the key change and that seemed to work. The rest of the lyric idea just kind of unraveled for us from there.”

The original Doobie Brothers would dissolve in 1982 and McDonald would go on to a successful solo career and continue to write with Loggins as well as collaborate with other artists.

The Doobie Brothers would re-establish themselves in 1987 and today have a full touring schedule with original members Johnston and Simmons and multi-instrumentalist John McFee, who originally joined the band in 1979. The band, elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2020, celebrated it’s 50th anniversary with a tour that stretched over 2021 and 2022, delayed a bit because of the pandemic. McDonald rejoined the band for the anniversary tour.

McDonald fondly recalls his time with the Doobie Brothers the first time around, though.

“It was just an opportunity, a door that opened rather suddenly with the Doobies. Those guys were so open to anything I had to offer and it caught me by surprise, really. I did not expect that having come from another situation with Steely Dan, where Don [Fagen] and Walter [Becker] were the sole source of all the material,” said McDonald. “I learned a great deal from them, however. That was probably my whole songwriting education in a way. I grew up writing songs, but it was a real crash course to learn a different approach to arrangement, chords, melody, working with Donald and Walter.

“So when I came to the Doobies, it was very fortuitous for me to have come from that gig, with all these kind of fresh ideas on how to write a song, what a song structure could be. And then all of a sudden to be surprised at how open — everybody from the producer [Ted Templeman] to the band members — and generous they were in allowing me to participate in the writing.”

EJ Wilson

I was there for your farewell concert at Six Flags over Georgia and I was just blown away. It was like a dream, seeing you all in person and you sounded SO good! I was shocked you were disbanding and therefore super thrilled that you got back together. All good wishes!