As a producer, Jim Messina became very aware while working at CBS studios that most of the engineers at the Epic Records label there were quite competent at what they had been doing, which was jazz, pop and classical music.

But when it came to rock and roll, Messina believed it just didn’t register with those engineers. They had been educated in a different way.

So when Buffalo Springfield split up in May 1968 before the release of its third and final studio album, Last Time Around a few months later, Messina and Richie Furay — who had been members of the Springfield at the end — joined with Rusty Young, George Grantham and Randy Meisner to form the band Poco.

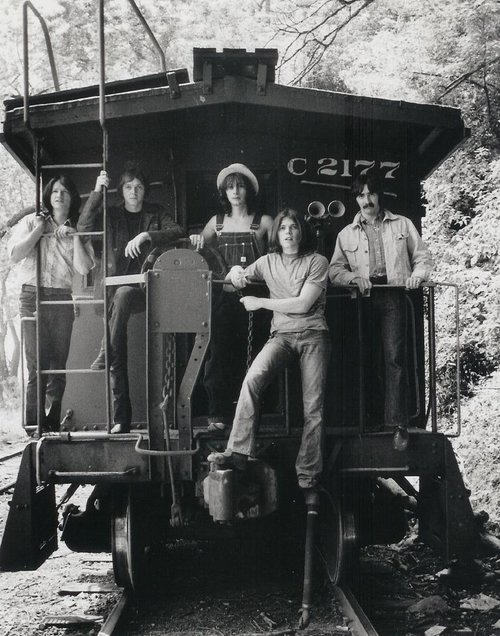

(Photo by Mike Morsch)

Poco’s first album, Pickin’ Up the Pieces, released May 19, 1969, on the Epic Label — which Messina would produce — was one of the earliest examples of what we now know as the “country rock” genre, but didn’t make a huge splash upon release, peaking at No. 63 on the U.S. Billboard 200 Albums chart.

Messina believes that one of the reasons is that it just didn’t sound as good as it could have. (Another was that the record was “too country” for rock radio stations and “too rock” for country radio stations.)

“I was extremely disappointed with it (Pickin’ Up the Pieces),” said Messina in a recent telephone interview from his home outside Nashville, Tenn. “The engineer was a nice person, but he was just all thumbs when he was in the studio.”

Originally, Messina was signed by Epic Records as an “engineer-producer-artist,” but it wasn’t until after the deal was signed that Messina realize he was not allowed to touch the board because of a collective bargaining agreement with the union that stated artists could not touch the recording console. If they did, a portion of the artist’s royalties would go to the union.

“My hands were tied at what I was really good at and able to do pretty intuitively. And that was suddenly cut off,” said Messina. “Then to try and explain to somebody who’d never really done it before why I wanted leveling amplifiers on overheads or why I wanted to compress the snare or the bass. Or why I wanted a distorted guitar sound and how to get that without hurting their equipment was confusing to them.”

So when Poco went into the studio to record its second album, the self-titled Poco, Messina, who was once again producing, wanted to work with an engineer who understood what it was the band was trying to accomplish.

“I met an engineer named Alex Kazengras. He was a new engineer there and had been working in rock and roll, and he had a great feel for sounds,” said Messina, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the release of that album. “He understood. So when I said we’re going to create a fuzz tone guitar distortion, he knew we were creating it in the studio and that he would pad the microphone with a 20dB pad, and record correctly. It became really wonderful to be back in the studio with an engineer who understood.”

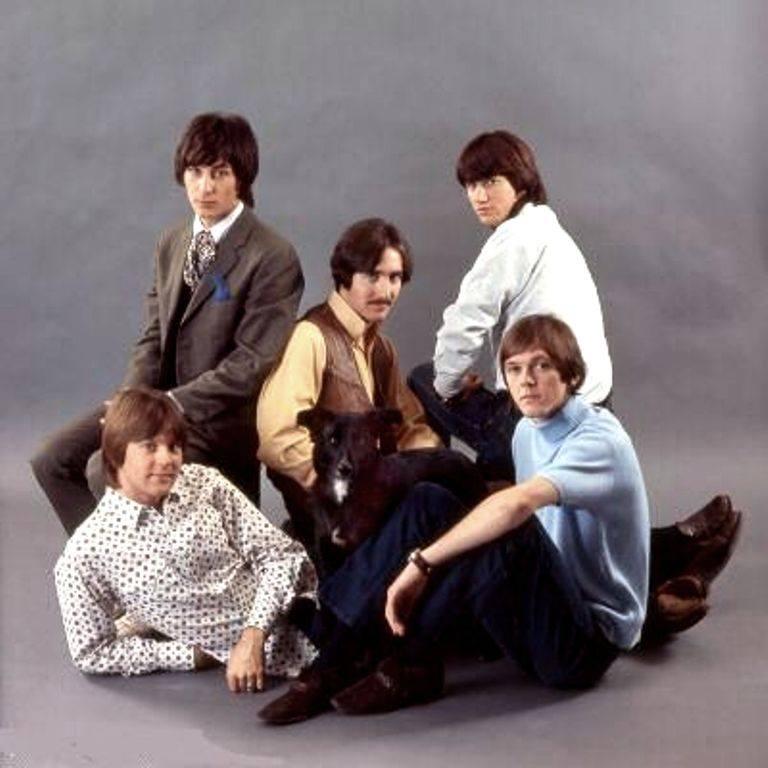

(Photo courtesy of Jim Messina)

Getting the right sound with the second Poco album — a sound that was something different than what Buffalo Springfield had done — was critical to Messina. For example, when Ahmet Ertegun produced the Springfield, he put the kick drum on one track, then put the other drums on one track. That didn’t create a very good stereophonic sound, according to Messina.

“So with Alex Kazengras, I said I’d like to do something different. I’d like to keep the kick drum on a separate track, but I’d also like to keep the snare drum on a separate track, the high-hat on a separate track and then everything else as far as overheads and tom-toms, goes on two tracks, which will make a stereo track,” said Messina.

Messina said that when one listens to Pickin’ Up the Pieces and compares it to the Poco album, the drums sound bigger and more dramatic on the second album.

“In those days, we had stereo, but we didn’t have pan pots early on,” said Messina. (Panning is the distribution of a sound signal, either through monaural or stereophonic pairs, into a new stereo or multi-channel sound field determined by a pan control setting. A pan pot, short for “panning potentiometer,” is an analog control with a position indicator that splits audio signals into left and right channels.)

“So what happens is you would put something in the center, especially if it was two tracks, and it would jump up 3DB (decibels) in the center,” said Messina. “We had to learn how to place those faders in a way where we wouldn’t get a huge bump in the center. Now with overheads, they’re going to pick up the snare a bit, which was good because it helps to get that balance in a drum kit. By bringing the snare a little underneath it, you get the definition. And with the high hat on one side, I’m able to bring the high hat up into that mix. And I was able to create a really nice, wonderful drum sound on that album.”

One of the songs on the album, the Messina-penned “You Better Think Twice,” would eventually go on to become one of the band’s signature songs. It was the first single from the band that got any attention, making it to No. 72 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart.

Messina said the song is about a girlfriend he had at the time.

“I was smitten with her and she had a boyfriend, but she was in and out with him. Then again, she was in and out with me, too,” said Messina. “I was kind of going through a little bit of an abandonment issue there with her. The song came out of wanting her to care for me and be with me. It was a little bit of a love song, but also a little bit of angst and frustration about somebody not wanting to necessarily be with me.”

The Poco album, released on May 6, 1970, got favorable reviews at time, getting to No. 58 on the Billboard 200 albums chart.

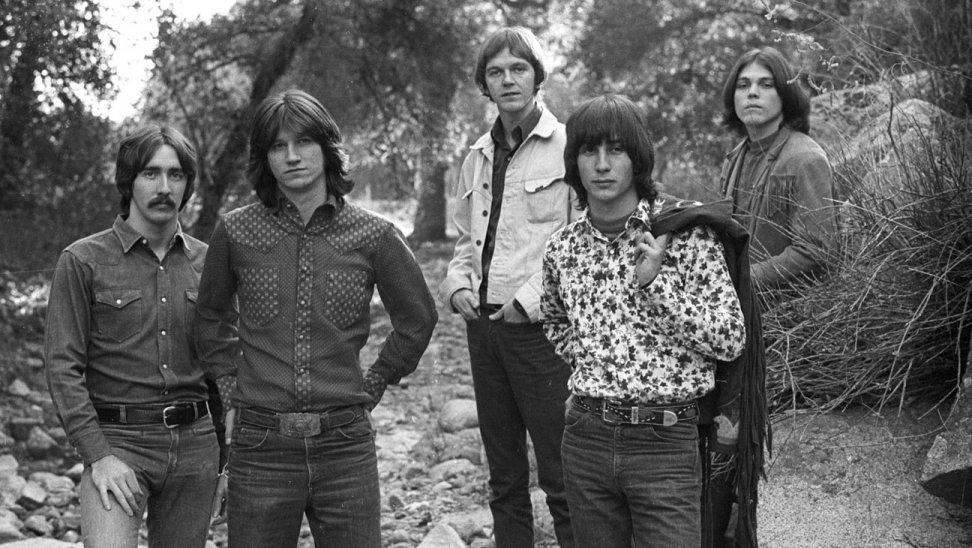

(Photo by Mike Morsch)

It would also be the first album featuring bassist Timothy B. Schmit in the place of Randy Meisner, who had quit the band over a dispute with Richie Furay — that Messina said he was unaware of at the time — during the mixing of Pickin’ Up the Pieces.

“Jimmy and Richie were in the studio. We’d finished the recording and had started the mix,” said Meisner in a Rockceller magazine interview with Ken Sharp in 2016. “I called down and said, ‘I’d like to listen to it.’”

But according to Meisner, Furay said no, only he and Messina were going to mix the record.

“I said, ‘Wait a minute, I made the music, too. I’d like to listen to the mixes.’ But Richie said, ‘No, just Jimmy and I are going to do it.’ So I said, ‘If you’re not gonna let me down there, I’m just gonna quit.’ And it was simple as that,” said Meisner.

Schmit, who was in a Sacramento, Calif.-based band called New Breed that had changed its name to Glad in 1968, had interviewed for a spot in Poco during its formation. (Messina and Furay also auditioned Gregg Allman and Gram Parsons — of the Byrds and later the Flying Burrito Brothers — for spots as well, but didn’t choose either of them.)

“I had a friend, this girl, who knew some of guys from Buffalo Springfield,” said Schmit in a 2017 interview for The Vinyl Dialogues. “She put it in their ear that I was around and I auditioned for them. They seemed to really like me and they asked me to come back in two days. It turned out they had somebody else come in the following day.”

That somebody else was Meisner, who recalls the story a little differently. Buffalo Springfield’s equipment manager, Miles Thomas, had tipped Meisner that Furay and Messina were looking for a bass player.

“After Miles told me that Jimmy and Richie were starting a group, they wanted me to do a tryout,” said Meisner in the Rockceller magazine interview. “I went out to Laurel Canyon and here’s Timothy Schmit just walking out as I’m going in. I played for a while and they said, ‘You’re in.’”

Schmidt believes he didn’t get the gig initially because Rusty Young, George Grantham and Meisner were all from Denver, Colo., and they already knew each other.

“The other thing was, there was a Selective Service issue on my part. So it was questionable as to weather I would be available,” said Schmit.

So when Meisner quit Poco — he would eventually go on to join the Eagles soon thereafter — Schmit was available and became the obvious replacement choice.

“Richie especially wanted me int he band, so I knew there must be something there,” said Schmit. “It was exactly what I wanted to do at the time and it was doubly sweet because I had been originally turned down for the gig. I thought that it was my only chance to really do music at that level and that I blew it.”

(Photo courtesy of Poco)

Messina liked Schmit as well.

“He was a great fit. Timmy brought some life, he brought some balance and creativity, had a good voice and the willingness to try new things,” said Messina.

When the band went into the studio to record the Poco album, Schmit said the other band members were looking for not only someone who could play bass, but who also was a good singer and songwriter.

“I hadn’t been much of a songwriter to that point, but I always wanted to be,” said Schmit. “I told them I was good at all three — bass playing, singing and songwriting — so I started writing songs.”

Of the seven songs on the Poco album, Schmit ended up co-writing “Keep on Believin’” with Furay.

“We just got together a few times and threw around some ideas for that song,” said Schmit. “I learned a lot from Richie.”

Although the Poco album did better than Pickin’ Up the Pieces on the charts, the band still hadn’t caught fire like its members and record company had wanted it to.

And there was some continuing internal strife that exacerbated the lack of record sales. In addition to that whole “too rock for country and too country for rock” thing, Messina thought the band hadn’t shown enough diversity in its music.

“Richie at the time was starting to get a little bit uptight, probably because the first record really didn’t happen for us,” said Messina. “I kind of felt squeezed a little bit by that as well. Richie had issues with Randy, so there was that stress going on as well.”

Epic Records loved the band, though, and wanted to see it succeed. But Messina was looking to get out.

“I don’t want to be critical because we are what we are when we’re there. For me, one of the reasons I wanted to leave was that musically, it wasn’t growing in a way where I felt things were going,” said Messina. “Look at Leon Russell, Bonnie and Delaney, Dave Mason, John Fogerty and Creedence Clearwater Revival — that music had some energy to it that I just didn’t think we were getting. I tried to do it with ‘You Better Think Twice,’ tried to move things, to do something that was a little more rock and roll, but still stayed with a country vibe.”

Messina believes that may have frustrated Furay.

“He really wanted to be successful and wanted his songs to be successful,” said Messina. “And he worked hard. But when you’re in a group, it takes a whole team to make things work and it means supporting each other. It just felt like Richie — I don’t know if it was envy or disappointment — but those feelings began to happen with me. I thought, well, I don’t want this thing to turn ugly. I’d rather just go back to producing and spend time with my wife.”

Messina went to Clive Davis, then president of Columbia Records, and told him he wanted to leave Poco.

“He was kind enough to say, ‘Look, get the next record finished and then find somebody to replace you who is good for the group and then you can leave the group in good standing so that they can be as successful as they can be,’” said Messina. “All of which I wanted to do anyway, but I thought it was great advice and it gave me incentive to stay there, deliver an album, make sure everybody was OK.”

Messina finished producing and mastering Poco’s third album, its first live album called Deliverin’ — and then left the band before its release in January 1971.

Paul Cotton was chosen to replace Messina.

“I roomed with Paul for a few weeks to teach him parts and make sure he was comfortable before he went onstage. I found him to be a gentleman and a great replacement for me,” said Messina. “So when I left, I left feeling good about having done it in a way where it wouldn’t cripple Poco. I’m not so sure they felt that way about me, but you can only do what you can do.”

Fifty years later, Messina is at peace with that decision.

“Having left Poco with one studio album that sounded that good, and with a great live album that had lots of spirited performances on it, I felt I was able to come back after a bad first-sounding album,” said Messina. “Pickin’ Up the Pieces has some good tunes on it, I just don’t think the engineering department allowed us to make the best record we could.”

Schmit, too, would leave Poco in 1977 to join the Eagles, once again replacing Meisner as the band’s bass player.

“We didn’t have a hit record with Poco, but this new thing (country rock) was Poco, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Pure Prairie League, that was kind of the evolution,” said Schmit. “We knew a lot of people weren’t doing it, but we also knew there was an audience for it. There was a lot of hype around Poco. We were going to be the next really big thing, but it didn’t quite pan out that way. I was fortunate to sort of grab onto something that was already happening.”

Leave a Reply