The Del-Satins were always looking for an echo. A doo-wop group from New York that formed in the early 1960s, they would search out an overpass in Central Park, a subway station, anywhere that provided a good echo to enhance their sound.

The five original members – Stan Zizka, Fred Ferrara, his brother Tom Ferrara, Keith Koestner and Les Cauchi – had decided to call themselves the Del-Satins as a tribute to their doo-wop heroes, the Dells and the Five Satins. When they weren’t looking for an echo, the Del-Satins would sing on street corners, like many other singing groups from that era.

The Del-Satins had some early success when they got an opportunity to sing with Dion DiMucci. One of the most popular artists of the late 1950s, Dion had split with his singing group, the Belmonts, and was looking for a new vocal group.

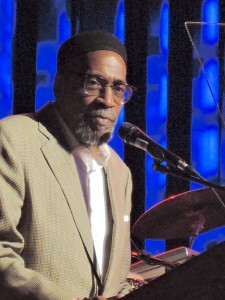

“Our manager sent us up to a studio – Laurie Records in New York – because Dion was looking for background vocalists,” said Les Cauchi, original tenor of the Del-Satins. “We did a couple of bars and he grabbed us right away. He said, ‘Yeah, this is the sound I want.’”

Dion immediately went to work on his next project, which was a single called “Runaround Sue,” written by Dion and Ernie Maresca.

“So Dion says, ‘All you gotta do is go “Hey-hey, bomda-heyda-heyda” in union. And maybe in the bridge, we’ll break into a little harmony and clapping.’ We thought he was out of his mind, I gotta tell you,” said Cauchi. “It wasn’t our forte, singing-wise. We liked the harmonies, we studied the harmonies, we practiced the harmonies. Dion got on a rhythm kick though, and it was great. But at the time, no way did we expect what happened.”

What happened was that “Runaround Sue” became a No. 1 smash hit in 1961. The Del-Satins would end up making three albums with Dion, and would sing on many of his other hits, including “The Wanderer,” “Lovers Who Wander,” “Little Diane,” “Love Came to Me” “Ruby Baby,” “Donna the Prima Donna,” “Drip Drop” and “Sandy.”

Changes started happening to the Del-Satins in the mid-1960s. And the biggest change occurred when the group was doing what it always did – looking for an echo.

“We were looking around this one school and went into the gym looking to do some singing,” said Cauchi. “And down at the other end, sitting on the stage, was this guy with a bass guitar. I said to Fred (Ferrara), ‘Oh my god, that’s Johnny Maestro. What is he doing here?’ He just happened to be there, playing some bass notes, probably trying to figure out a tune.”

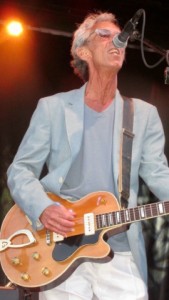

Maestro had begun his singing career in 1957 as the lead singer of The Crests, a doo-wop group that had several hits in the late 1950s and early 1960s, including “16 Candles,” which made it to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles chart in 1959. The Crests were the first interracially mixed doo-wop group of the era.

But by late 1960, Maestro would leave the Crests for a solo career. Although he did have a couple of Top 40 hits as a solo artist, including “What A Surprise” and “Model Girl,” Maestro was unable to reach the chart heights that he had achieved with The Crests.

By 1967, the Del-Satins were looking for a new lead singer to replace original lead singer Stan Zizka, who had left the group a few years earlier to pursue a solo career of his own. When Tom Ferrera and Cauchi got drafted into military service, Maestro joined the Del-Satins.

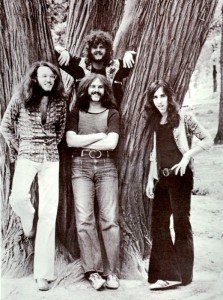

In 1968, when Cauchi returned from military service and rejoined the group, it then changed its name to The Brooklyn Bridge and became an 11-piece group, including a horn section, with Maestro as the lead singer.

“That name was actually given to us by an agent because there was a saying, ‘It’s easier to sell the Brooklyn Bridge than it is to sell an 11-piece group,’” said Cauchi. “Wait a minute, let’s call ourselves The Brooklyn Bridge and that’s what happened.”

The new group’s first recording project featuring Maestro on lead vocals was for Buddha Records and would be the self-titled “Brooklyn Bride” album, scheduled for release in late 1968.

“We were short a song for the album, so we were searching through other albums. We liked the 5th Dimension, we liked their style, the voices, the instruments, the things they did,” said Cauchi. “We heard this one song and we went to the producer (Wes Farrell) and said we had an idea to do this song. It’s a good song, it’s definitely within Johnny’s range and it’s the style that Brooklyn Bridge is able to do.”

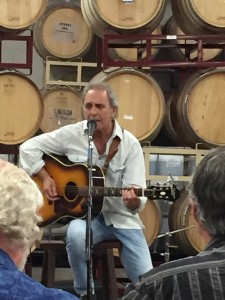

The song was “The Worst That Could Happen,” written by Jimmy Webb, which had first appeared on a 1967 album of nearly all Jimmy Webb songs called “The Magic Garden” by the 5th Dimension.

Although the song didn’t do much for the 5th Dimension, the recording by Johnny Maestro and the Brooklyn Bridge made it to No. 3 on the Billboard Top 100 Singles chart in February 1969.

“When we finished recording it, we realized that it was something more that just a B-side or an album cut,” said Cauchi. “And the record company realized the same thing. It got on the bandwagon and got the promotion people out there and started to push the song.”

“The Worst That Could Happen” has been a signature song for the Brooklyn Bridge ever since.

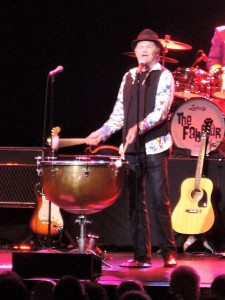

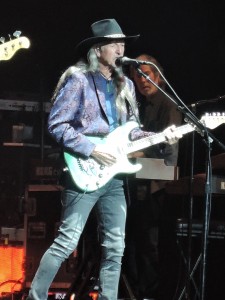

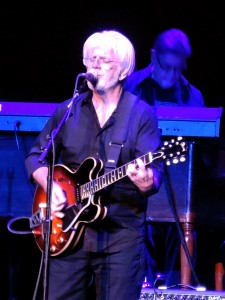

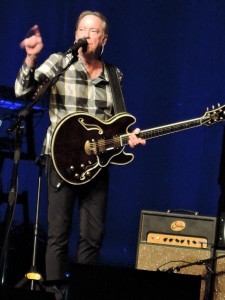

Although the Brooklyn Bridge continues to tour – it will be one of the groups featured at the Golden Oldies Spectacular show March 3 at the State Theatre in New Brunswick, N.J. – it does so without some of its original members. Maestro died in 2010 at age 70 and Fred Ferrara died in 2011. Original member Cauchi remains with the group, as does original Brooklyn Bridge saxophonist Joe Ruvio and bass player Jimmy Rosica. In 2013, Joe Esposito took over as lead singer.

“We lost two very important people (Maestro and Fred Ferrara) not only to the band, but to our lives,” said Cauchi. “It was tough but we got through it. Their spirits are always with us on stage and will never go away. It’s part of who we are. But we feel strong enough to carry the legacy and that’s what we’ll be doing.”