Musicians work primarily on Friday and Saturday nights. And the women in their lives, well, they don’t like that too much.

That’s the way it was in the mid-1960s for Felix Cavaliere of the Young Rascals. By the end of 1966, the band’s self-titled debut album had reached No. 10 on the Cashbox album chart and No. 15 on the Billboard Top 200 albums charts. The record featured the group’s first No. 1 single, “Good Lovin’” and positioned the band to begin writing and recording more of their own material.

It made the Young Rascals in demand as well, particularly on Friday and Saturday nights, much to the dismay of their wives and girlfriends.

“That’s not exactly their cup of tea because, hey, you can understand when they say, ‘What do I do while you’re out there entertaining?’ So it’s a normal situation and any musician will tell you that they go through a lot of changes with that,” said Cavaliere. “And so groovin’ on a Sunday afternoon became the only time that we had together.”

It also became the inspiration — along with Cavaliere’s girlfriend at the time — for what would become the next No. 1 hit for the Young Rascals.

“Groovin’” was the title track from the band’s third album, released in 1967. Written by Cavaliere and bandmate Eddie Brigati, the song reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 charts and stayed there for four weeks.

Cavaliere’s girlfriend at the time was a young woman named Adrienne Buccheri, and he believes that she served as a muse for him at that point in his career.

“That was the age where all of us were kind of like dating and getting engaged. That’s what happened to me, basically. I fell madly in love with this woman who actually turned out to be a muse, no question about it,” said Cavaliere. “That’s really the only reason she was in my life. It was very strange. We were engaged, but never married. I really feel like she was like the old poetic muses. They just come into your life for a reason and spark that kind of emotion and feeling that generates those types of songs.”

It was no coincidence then, given the relationship of Cavaliere and Buccheri at the time, that the next single off the Groovin’ album to become a Top 5 hit for the band was “How Can I Be Sure,” which got to No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.

Felix Cavaliere said that the environment in which Atlantic Records put the band in was positive and helped contribute to the band’s success.

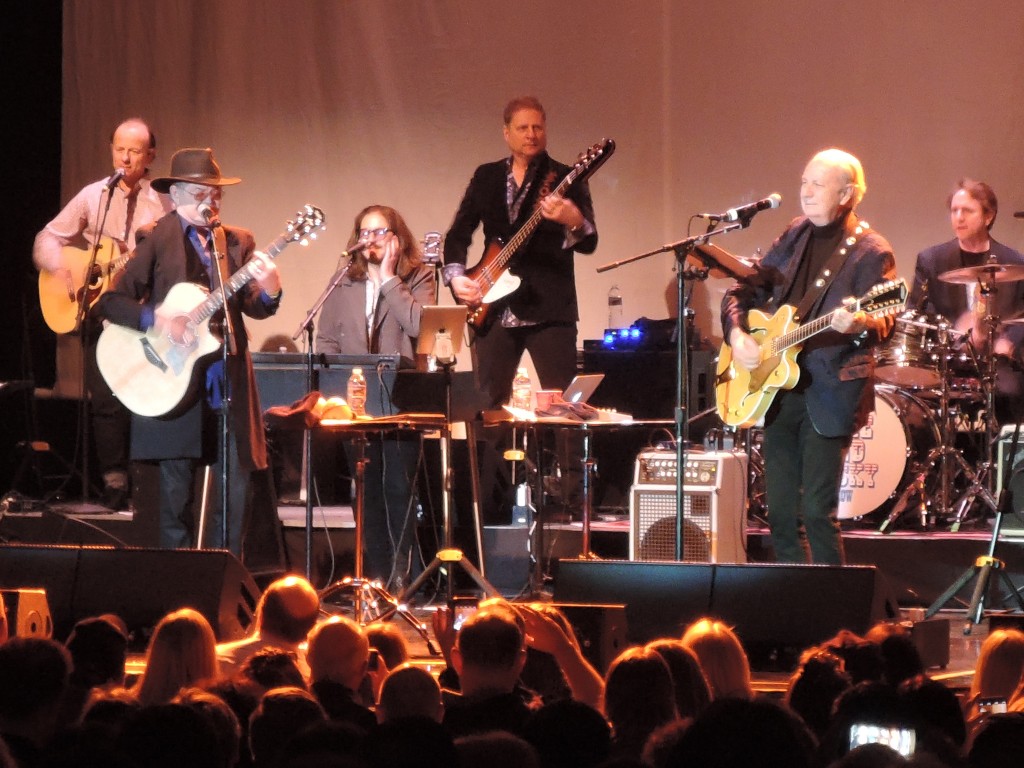

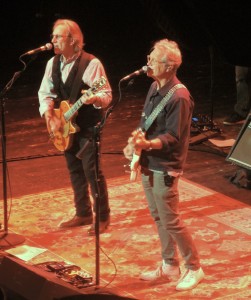

(Photo by Jack Leitmeyer)

“She was very young, much younger than I was, and it was totally crazy. It culminated in ‘How Can I Be Sure.’ I woke up one day and said, ‘What the hell am I doing? I’m going out with a kid.’ It was strange,” said Cavaliere. “She ended up marrying a very dear friend of mine and they had couple of children together, then unfortunately she passed. That’s the story. It’s kind of strange, you know. I have to be careful with it now because my present-day wife doesn’t like that story too much.”

Brigati was also battling his own personal struggles during the making of the album, none greater than what he was experiencing when trying to finish the song “How Can I Be Sure.”

“We were trying to finish an album. We had to go in Friday and finish it because we had to go on the road Saturday and Sunday,” said Brigati. “I had kind of a breakdown over it. I couldn’t finish it and we had to go in (to the studio). The melody wasn’t actually created yet, the storyline wasn’t created.

“On that particular song, I got a block and I was freaked out about not finishing it. My brother (David) put a bunch of different things in it and he was never properly acknowledged for it,” said Brigati. “It’s 50 years later and I’m still asking, ‘How can I be sure?’ It was a genuine situation with being honest with what was going on.”

According to Cavaliere, the music business in the mid- to late-1960s was a singles-oriented world. Radio at the time was based on the Top 40 and the challenge for bands of that era was to get enough air play to score a hit single.

“It certainly wasn’t easy with the competition that was out there, which was phenomenal,” said Cavaliere. “But it also raised the bar to a high level, so a lot of music from that time is still here.”

The band’s label, Atlantic Records, ended up releasing eight of the 11 songs on Groovin’ as A- or B-side singles. Cavaliere and Brigati co-wrote eight of the songs, while guitarist Gene Cornish wrote two, “I’m So Happy Now,” which was the B-side of “How Can I Be Sure,” and “I Don’t Love You Anymore,” one of the three songs that wasn’t released as a single.

As was the case with many bands then, the pressure from the labels to continue to produce hit singles and albums was intense. Cavaliere and Brigati were well aware of that pressure.

“And the reason was because Atlantic was not a major label at that time, so money was an issue. Anytime you combine money with art, it’s difficult,” said Cavaliere. “So there was a lot of pressure from Atlantic to keep product going out. The other thing was, it was a challenge. But there was also a tremendous amount of good luck, good fortune and being in the right place at the right time. Yes, you felt the pressure but you felt it from a different angle, from the people who were behind the label.”

Eddie Brigati said the language and lyrics of the songwriting collaboration between himself and Felix Cavaliere was upbeat and positive.

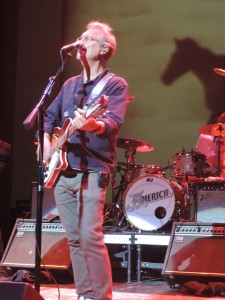

(Photo by Mike Morsch)

Brigati said the the combination of the lack of nurturing by the record company and the fact that the band didn’t have much, if any, down time away from the cycle of recording and touring, took it’s toll, both physically and creatively on the band members.

“There wasn’t a rest period, there wasn’t a recalculation,” said Brigati. “Basically I was broke and broken. And there was no rehabilitation. There was no such thing as taking six months off. You can’t, you have to strike while the iron is hot.”

Despite that pressure, Cavaliere also admits that the environment in which Atlantic Records put the band was positive and helped contribute to the band’s success.

“I always equate it as a very fertile type of land. All we had to do was pop a seed in there, man. And it grew, because the team that we had at our disposal was phenomenal,” said Cavaliere.

That type of creative freedom also was evident in the writing process for the songs on the album according to Cavaliere. And although it was hard work, he and Brigati were in the groove during their writing sessions for “Groovin.’”

“There are two people writing these songs. I’m writing most of the music and the titles and themes. My partner was filling in the verse repartee. It wore him out, man, I’ll be honest with you,” said Cavaliere. “Music to me comes very natural. For me to sit down and write a song, it’s pretty easy. So I was way ahead in terms of the music being before the lyrical content. If you look at this job that you have as a blessing, then that makes life easy. But if you look at this job as a J-O-B, it will wear you out. It didn’t wear me out because I loved every moment of it and I mean that truthfully.

“As a writer, when you get a concept in your brain and then all of a sudden it manifests itself in a studio on speakers, it’s beyond belief. How cool is that?” he said.

“The language and the lyrics of our songs were all upbeat,” said Brigati. “Felix and I collaborated on the majority of the songs. It was a positive viewpoint . . . what if? ‘It’s a beautiful morning, I think I’ll go outside for a while.’ These are all kind of flippant ideas, but all going toward the positive human, cooperative energy.”

Cavaliere said that he, Brigati, Cornish and drummer Dino Danelli were all pretty happy when they heard the finished album, like they were for all the albums they created.

“We were always very proud of what we did. You walk out of the studio and certainly there were periods of turmoil within the organization during the recording. But we always walked out of there smiling, saying ‘Wow!’” said Cavaliere.

Gene Cornish wrote two songs for the ‘Groovin” album, “I’m So Happy Now,” which was the B-side of “How Can I Be Sure,” and “I Don’t Love You Anymore,” one of the three songs that wasn’t released as a single.

(Photo by Mike Morsch)

“You also walk out of there pretty tired. It was a lot of time. And I was present for every second of it. We never mailed anything in. I was there for everything and I enjoyed every aspect of the process, from the creation of the songs to the recording of the track to the singing and the mixing, even to the mastering whenever possible. First of all, I wanted to learn, and second of all, that’s your product. You gotta be there,” he said. “I guess you always like it as a finished album, but you’re apprehensive about whether other people are going to like it.”

That apprehension about the Groovin’ album turned out to be unfounded. Everybody liked it. The album reached No. 5 on the U.S. Billboard Top 200 Albums chart and No. 6 on the Cashbox albums chart.

In addition to the album’s title track making it to No. 1 and “How Can I Be Sure” getting to No. 4 on the singles chart, two other Brigati-Cavaliere collaborations, “A Girl Like You” and “You Better Run,” reached No. 10 and No. 20 respectively on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 Singles chart.

“The situation with Groovin’ in those days, all of us were kind of like tuned in to one another musically. And by that I mean the people in England — the Beatles people, the Stones people, the Kinks — and the Beach Boys, even though we were in a geographically different place,” said Cavaliere. “We were all falling in love.”

The cover for the Groovin’ album — which shows the band members drawn in caricature — was conceived, but not illustrated by drummer Danelli.

“I was pretty heavily into art in those days, so I kind of directed where we went with our graphics and things like that,” said Danelli. “I didn’t do the actual cartoon drawing on the cover. That was done by a friend of mine, Lynn Rubin. But we talked about the concept, what we wanted to do, which was take a comic book approach to it. That was kind of the style in those days. I used to love doing the whole trip of the packaging of an album. It was just a ton of fun.”

The cover also featured a sticker on the front that read “This LP has the big hit” followed by either “How Can I Be Sure” or “A Girl Like You,” both of which were Top 10 hits.

The Young Rascals would eventually change their name to the Rascals after the release of the Groovin’ album. The band would experience more chart success with two more Top 5 singles, “People Got to Be Free,” which got to No. 1, and “A Beautiful Morning,” which got to No. 3, both in 1968. The band would record seven albums from 1966 to 1971 with the original members before breaking up.

The Rascals reunited in 2012 for the “Once Upon a Dream” reunion — a combination concert and theatrical event — which lasted for 15 performances. The shows were produced and directed by Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band member Steven Van Zandt and his wife, Maureen Van Zandt.